Tsiteli Gorebi 5 Area

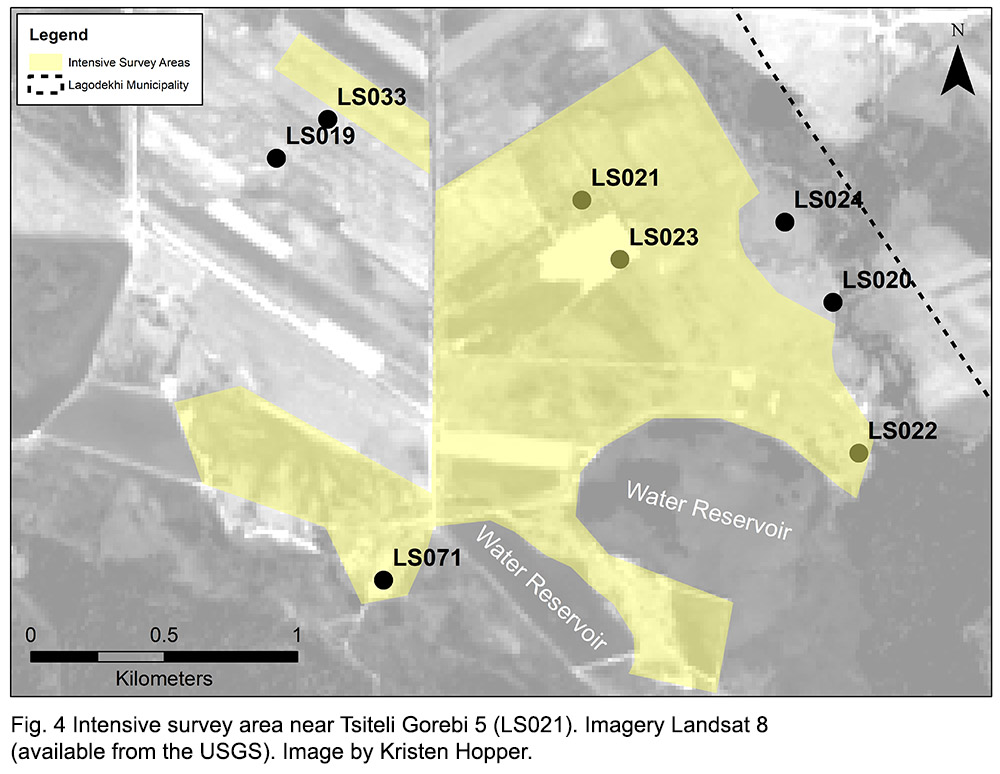

In our southernmost survey area we recorded one new site in 2019, designated LS071 (Fig. 3, Fig. 4 ). A preliminary visit to the site had been made in summer of 2019 (the site was given the temporary ID of 1001), but not fully recorded.The site is represented by a scatter of obsidian and pottery on both the western and the eastern side of a modern water reservoir. Most of the material from the east of the reservoir comes from the spoil heaps on the banks of the reservoir. We think it is likely that the site was destroyed by the reservoir, and the artefact scatter mainly represents the redeposited material. The extent of the site is therefore difficult to determine.

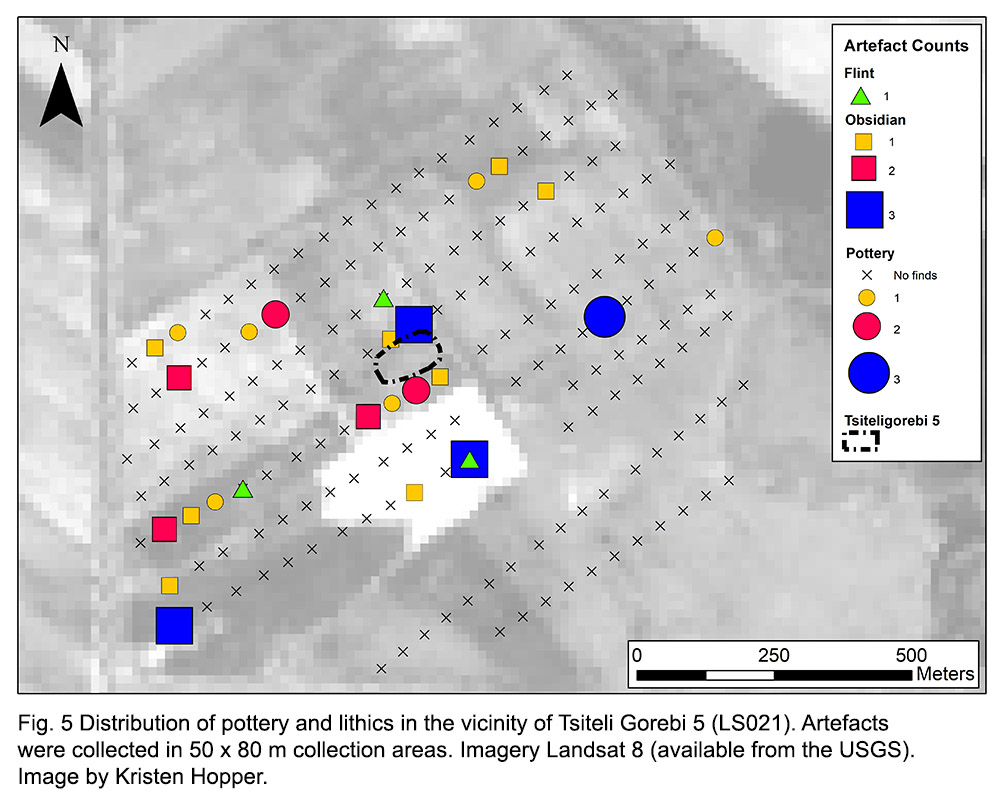

We also undertook transects in the accessible areas between the area of LS071 and Tsiteli Gorebi 5 (LS021), as well as immediately to the north of Tsiteli Gorebi 5 (Fig. 4, Fig. 6). The density of artefacts per 50 x 80 m collection areas is illustrated in Fig. 5. Interestingly, despite the ploughed fields, the density of artefacts recovered was unexpectedly low, even over the area of the mound itself. In general, this illustrates the difficulty we have hadin locating surface artefacts in areas that have been heavily cultivated over long periods of time.

North of Ulianovka

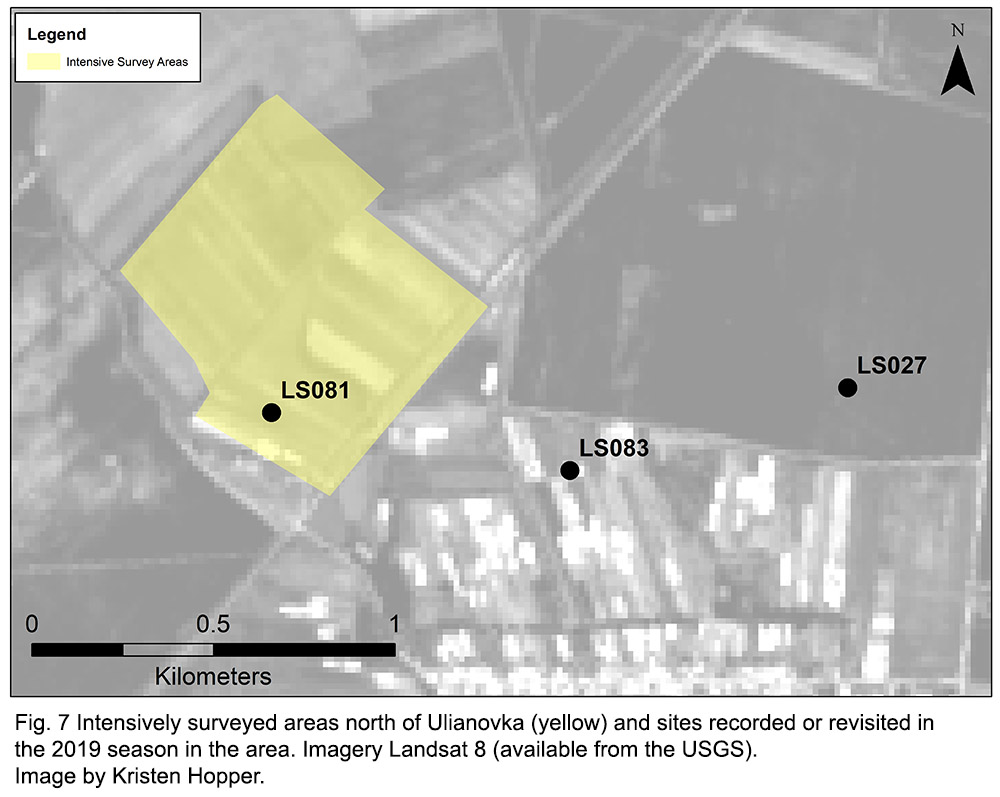

We also undertook transect survey (with 50 m long collection areas) in cornfields immediately north of Ulianovka (Fig. 7). Here the fields had been harvested but not ploughed. Visibility was approximately 60%; however, we located a large artefact scatter containing primarily Late Bronze Age material (LS081).

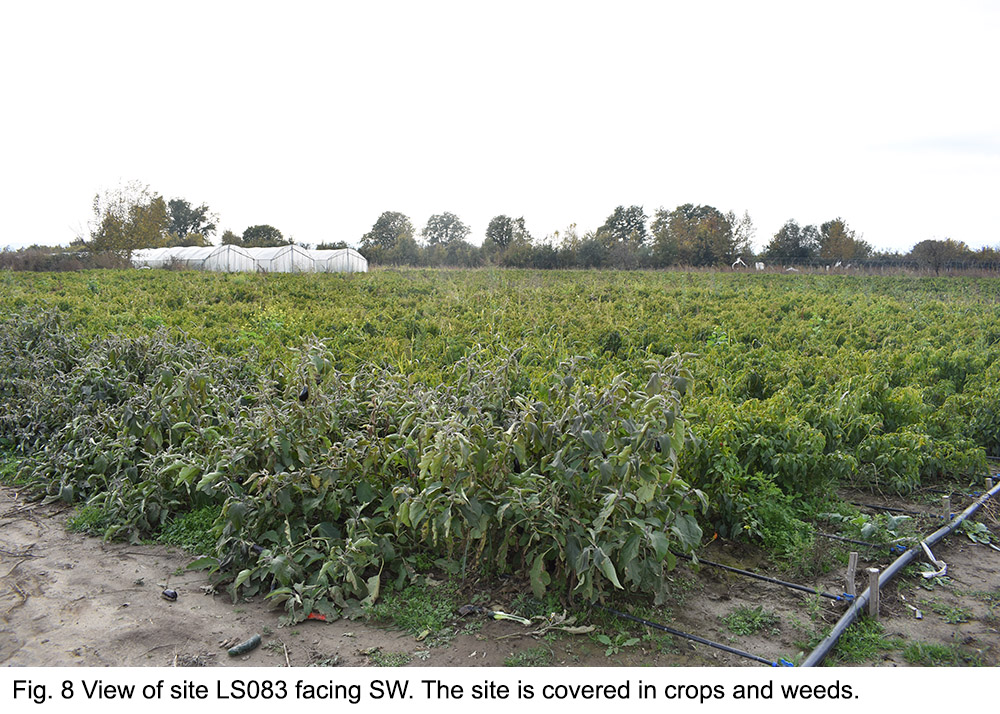

We also recorded a site on a farm on the northernmost edge of Ulianovka (LS083). The site had a preliminary visit in summer 2019 and had been given a temporary ID of 1003. Artefacts associated with the Hellenistic period had been reported here in the past and a small collection of material made in the previous visit. We attempted to define the edges of the artefact scatter, though this was made difficult by the fact that the main density was located within a field of peppers and aubergines that was now overgrown (Fig. 8). However, we were able to determine that the site likely covered at least 20 m in N – S direction. There was also a very subtle topographic rise visible within the field.

Local residents indicated that there had been a small hill on this location that had been ploughed out. Inspection of historical imagery on Google Earth confirms the presence of a small mound in this location that was flattened sometime between 2009 and 2018. It measured approximately 25 x 50 m (see Fig. 9).

We were also directed toward another area where a small hill or kurgan may have been situated. This was LS027, a site we had located in the 2018 season, but were unable to determine the extent of due to it being completely covered by a cornfield (see Fig. 7). Now that the field was no longer under corn cultivation, we were able to collect material covering an area of at least 150 m E-W and 130 m in N-S direction. The material recovered likely represents Hellenistic and Medieval activity.

Uplands Near Pona

We chose the slopes near to the village of Kveda Pona to investigate activity in the uplands (Fig. 10). Here, grazing is the primary mode of land use and surface visibility is generally good, except within the forested gulliesand ravines. Remains of terrace field systems are present, but their date is unknown.

Here, we had previously recorded Pona Church (LS053). The area has a general low-level background scatter of medieval pottery. We located one site (LS073) consisting of a hilltop with the remains of ruined buildings and graves. The surrounding slopes had a considerable amount of roof tiles and pottery. The graves may represent Islamic burials from the early 20th century as most consisted of simple headstones and footstones. Local archaeologists suggested that the building fragments may have been part of the original site of Pona church which is said to have been destroyed by Shah Abbas in the late 16th/early 17th century.

We also located several stone structures (LS077, LS079, LS080), and what appears to be a kiln/oven and nearby stone wall (LS078)(Fig. 11). Most of the pottery recovered appears to be Medieval (at least post 10th century). In general, the activity in this area appears to relate to the Medieval period.

Karvasla

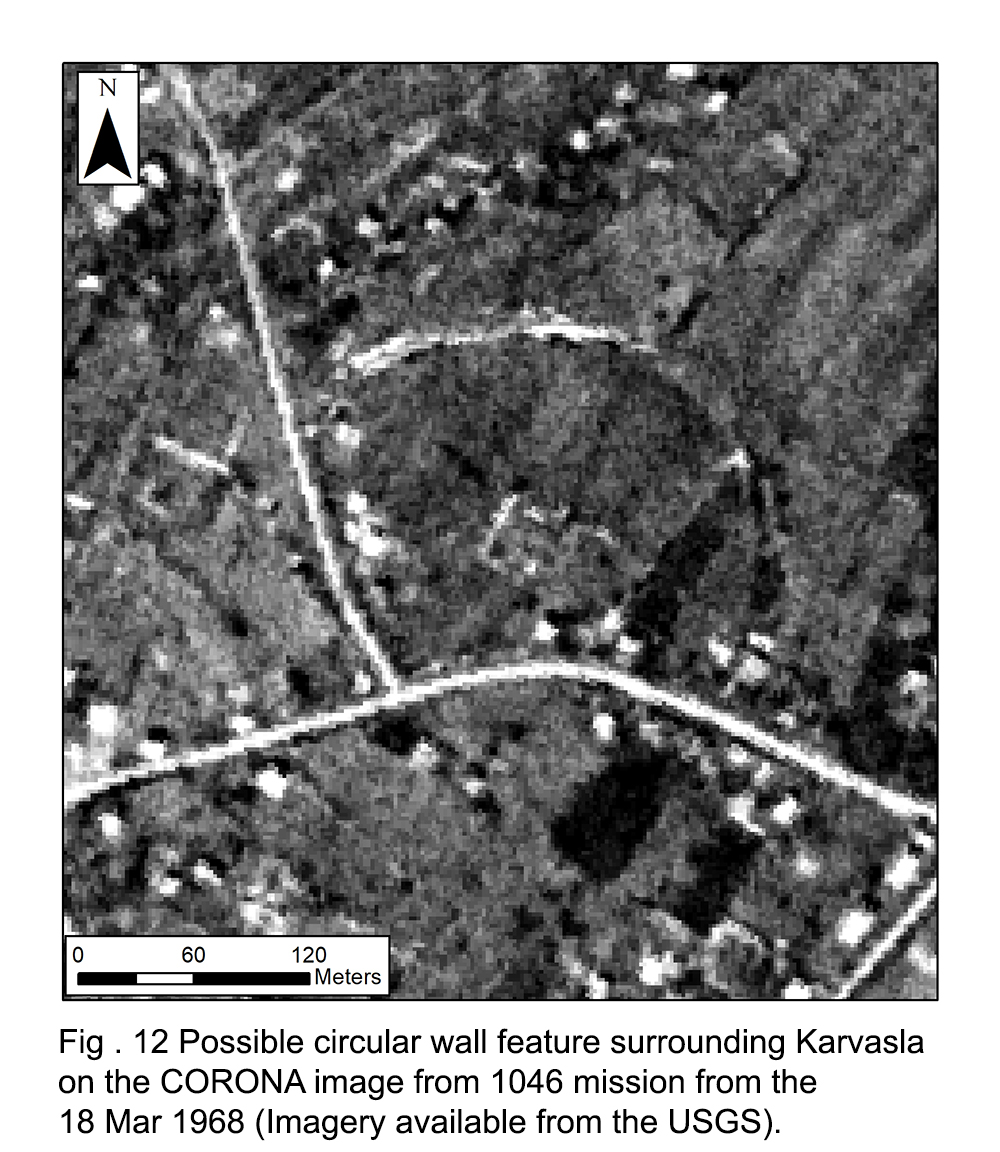

We also investigated a possible wall feature that was visible on the CORONA imagery around the site of LS050 – a karvasla (or caravanserai) – that we recorded in 2018 (Fig. 12). Between modern houses, we located what are probably the remains of this feature – this included large stones and some linear mounding that may represent the base of the wall.

Mounded sites in the woodlands

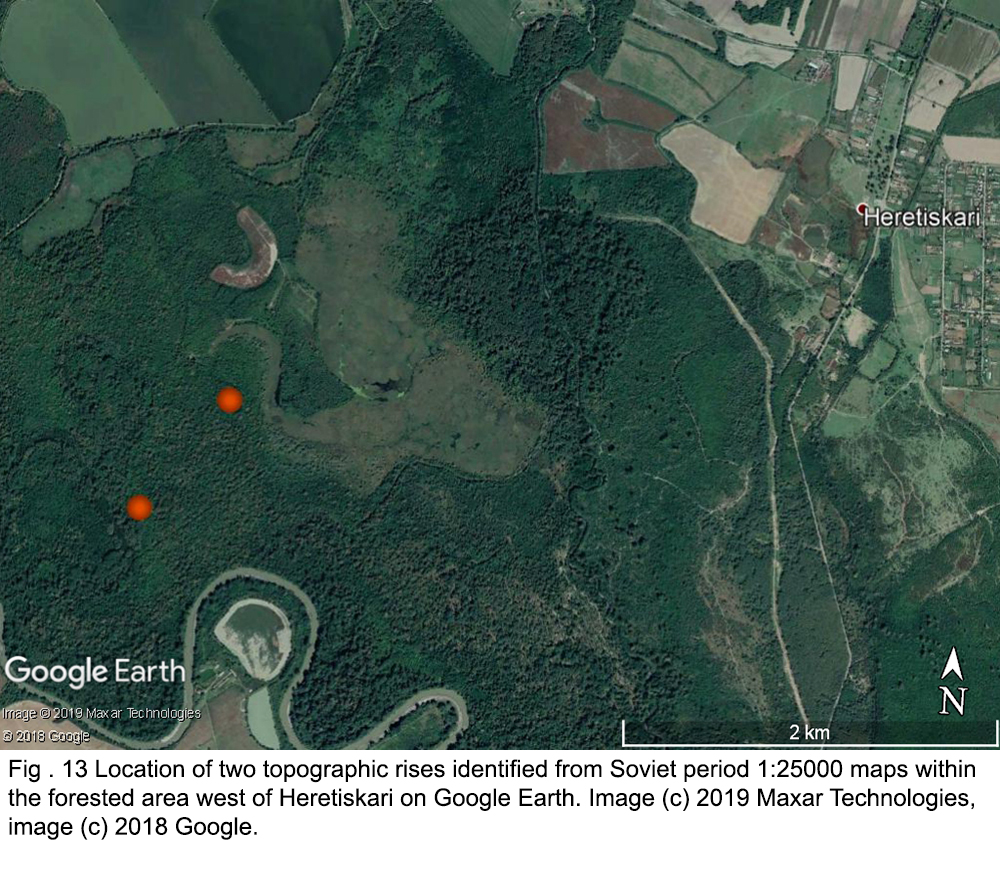

In the wooded areas near the Alazani River (in the southern part of Lagodekhi Municipality), we investigated two topographic rises indicated on Soviet period 1:25000 maps (Fig. 13).

LS075 was a large mound of c. 200 m in diameter and irregular in shape. It was clearly not a kurgan as we originally suspected. Some pottery fragmentswere found on the surface and suggest activity primarily in the Medieval or modern period but, interestingly, possibly also in the late prehistoric/Early Bronze Age. It is potentially a mounded settlement.

LS076 was an ovoid mound on which we located some pottery, mostly in animal burrows on top of the mound. Again, this feature is more likely to have been a settlementthan a kurgan. The pottery dates to the Medieval Period.

Possible Kurgan sites

We also checked a number of features (soil discolourations, vegetation differences and mounded features) identified by Stefania Fiori as possible kurgans on modern and historical satellite imagery. These are detailed in her master’s thesis (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, 2020).