The Chalcolithic assemblage (Fig. 14) does not show any significant difference with what was recovered in the 2018 soundings at the site, and our general interpretation of it remains the same. Most items were in extremely fragmentary conditions and their surfaces were considerably damaged and/or encrusted. A large amount of the material comes from the superficial humus or from disturbed layers (notably, from the filling of the large Soviet canal and of modern pits). The Chalcolithic layers were not rich in pottery and none of it was found in situ; most of the sherds came from generic filling layers or from the filling of pits. Considering these circumstances, we can provide only a general evaluation of the fabrics, shapes and decoration repertoire.

Chalcolithic pottery is very homogeneous from the point of views of technology, morphology and decorations. All of it is handmade and its quality is coarse; the fabric contains a large amount of mineral inclusions of medium or large size, usually of brown and white colour, possibly of calcite or other metamorphic rocks, such as mica-schist. The presence of obsidian was observed only on fragments belonging to one of the three different wares which have been distinguished (see below).

According to the procedures established during the 2018 season, quantification of the Chalcolithic pottery was done by dividing the sherds into three different wares (Light Brown Orange Ware, Red Ware, and Grey Ware), and then counting them and weighing them on an electronic scale. The difference between the three wares is based on fabric, firing, section, surface colour, and surface treatment. Thirty non-diagnostic sherds were selected as samples for thin sections and petrographic analyses to be carried out in Italy in order to confirm or disprove the preliminary fabric classification based on macroscopic observation.

Light Brown Orange Ware is the most frequent and more homogeneously distributed over the whole excavated area; the total amount of LBOW sherds amounts to 1.104 fragments, which represent 70% of the Chalcolithic assemblage and include 124 diagnostics. The fabric is mostly oxydised, with some exceptions where the core is reduced, but the surfaces are oxydised; the colour of the outer surface is orange or light brown with yellowish shades (5YR 5/4 reddish brown, 5YR 6/3 light reddish brown, 10R 5/4 weak red). Sometimes the surfaces are smoothed.

Grey Ware is the second most common ware. It amounts to 300 sherds (19% of the total), 34 of which are diagnostics. The surface of the sherds is rarely smoothed, with a grey shade (5YR 3/1 very dark grey, 10YR 5/2 greyish brown); the fabric is reduced.

Red Ware, represented by 181 items (11% of the total sherdage), is the rarest, and includes no more than 15 diagnostics. Thanks to firing in an oxydising environment, it is characterised by a reddish surface (10R 5/4 weak red, 10R 5/6 red), which is sometimes finished by smoothing or, rarely, by slight burnishing. The fabric of this ware is notable for the presence of obsidian, which was intentionally added as a temper.

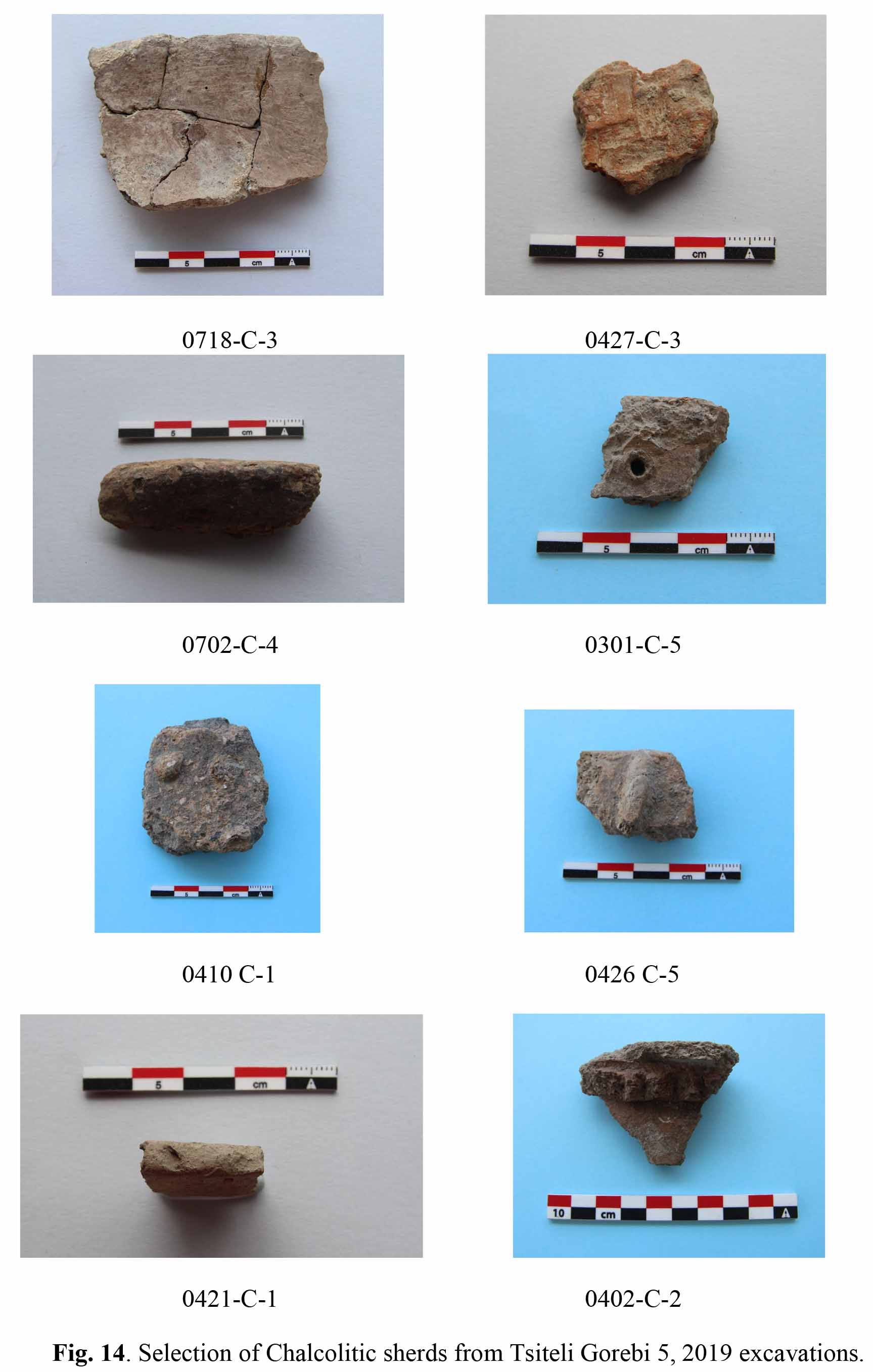

The morphological repertoire is shared by the three different wares. It mainly consists of large deep bowls with plain rims, wide-mouthed pots with slightly out-turned or vertical rims (Fig. 14, 0718-C-3), and hole-mouth jars with inturned rims. Bases are flat or flattened, sometimes slightly raised: mats impressions are relatively frequent on their lower surface (Fig. 14, 0427-C-3). The presence of handles was not recorded, but some items have elongated oval-shaped lug-like protrusions instead (Fig. 14, 0702-C-4). This basic repertoire is joined by a fair number of high straight-walled trays bearing a line of passing holes, made before firing, just under the rim (known in literature as mangal) (Fig. 14, 0301-C-5).

Decorations are mostly represented by circular knobs in relief (Fig. 14, 0401-C-2). There are only two sherds with relief decorations – zig-zag patterns, etc. – similar to the ones known from sites of the Shulaveri-Shomu culture (Fig. 14, 0426-C-5), and no examples of painted decoration. Some rims have notches or nail impressions on the top (Fig. 14, 0402-C-2), and some sherds show relief bands decorated with finger impressions located between the shoulder and the neck (Fig. 14, 0421-C-1).

Both shapes and decorations are similar to those of the assemblage illustrated by Varazashvili from the 1970s excavations at Damtsvari Gora, Kviriatskhali and the other Tsiteli Gorebi sites (V. Varazashvili, Rannezemledel’cheskaja kul’turaJuro-Alazanskogo Bassejna [The Early Farming Culture of the Iori-Alazani Basin], Tbilisi: Metsniereba 1992). There are also numerous parallels with the site of Tsopi (L. Nebieridze, The Tsopi Chalcolithic Culture, Studies of the Society of Assyriologists, Biblical Studies and Caucasiologists 6, Tbilisi: Artlines 2010), in particular for the trays with rows of pierced holes and for the oval-shaped lugs. However, contrary to this site, Chaff-Faced Ware is totally missing at Tsiteli Gorebi 5. Except for the complete absence of vegetal tempering, our assemblage looks rather similar to that from Period II at Mentesh Tepe in the Tovuz district of Azerbaijan; which a few 14C dates would situate in the second quarter of the 5th millennium BC. (B. Lyonnet in B. Helwing et al., The Kura Projects. New Research on the Later Prehistory of the Southern Caucasus, Archäologie in Iran und Turan 16, Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag 2017, 144-147; B. Lyonnet, Rethinking the ‘Sioni cultural complex’ in the South Caucasus (Chalcolithic period): New data from Mentesh Tepe (Azerbaijan), in A. Batmaz, G. Bedianashvili, A. Michalewicz & A. Robinson (eds), Context and Connection: Essays on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East in Honour of Antonio Sagona, Leuven, Paris, Bristol CT: Peeters 2018, 547-567). We therefore confirm the tentative dating to a rather early phase within the Chalcolithic period that we proposed after the 2018 excavation season. In fact, the apparent continuity (both in fabrics and in decorations) with the Ceramic Neolithic production suggests a date in the early 5th mill. BC., for Tsiteli Gorebi 5, i.e. much earlier than what Varazashvili suggested for the other sites of the cluster.