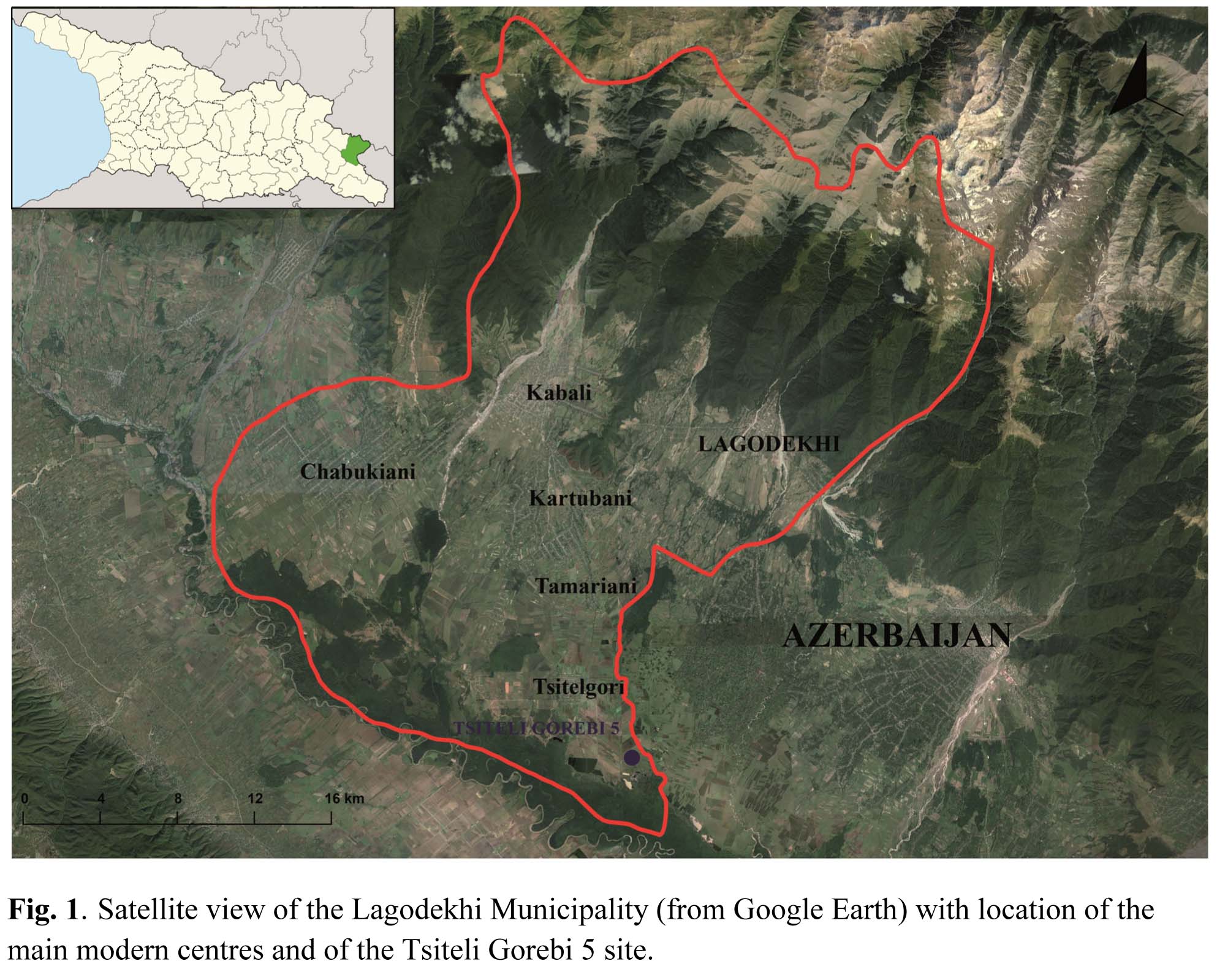

The aim of the season was to obtain a preliminary evaluation of the potential of the Lagodekhi municipality in the Kakheti region of Georgia for a future multiyear archaeological project to be carried out in cooperation with the local authorities. The municipality extends over an area of ca 900 km2 at the eastern limit of Georgia, near the present border with Azerbaijan (Fig. 1). It is located between the foothills of the Greater Caucasus range and the valley of the Alazani river, one of the main tributaries of the Kura, in the connection area between the alluvial fans of the Caucasus range and the river plain.

Kakheti is one of the richest archaeological regions of Georgia. The Alazani valley, in particular, is famous for the monumental barrow graves (kurgans) of the so-called Early Kurgan period – mid-second half of the II millennium BC – (Sh. Dedabrishvili, Kurgans of Alazani Valley, Tbilisi 1979). Besides the Early Kurgan period, other phases which according to previous scholarship are well attested in the region are the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age (2nd half of the second/early first millennium BC) (see K. Pitskhelauri, Principal Problems Concerning a History of the Tribes of Eastern Georgia of the 15th-7th Centuries B.C. (according to the archaeological materials), Tbilisi 1973) and the Chalcolithic period (5th/first half of the 4th millennium BC), which is also very well attested in the neighbouring regions of Western Azerbaijan. The latter, and its later phases in particular, represents an important, though still poorly understood phase in the history of the Southern Caucasus, which witnessed deep transformations and complex relations between the local communities and the proto-urban civilisations of Upper Mesopotamia. The relative and absolute chronologies of the different local cultures (Sioni, Tsopi), as well as the impact on them of the so-called Chaff-Faced Ware tradition, and the origins of the Kura-Araxes culture, are all still far from clear.

Contrary to other parts of Kakheti, the Lagodekhi Municipality remains relatively poorly explored. In spite of some recent sensational discoveries (see Z. Makharadze et al., Ananauri Big Kurgan n. 3, Tbilisi 2016), regular excavations in the region have been rare after the Soviet period, when the intense agricultural exploitation of the territory caused a deep impact on the preservation of archaeological remains. In particular, investigations carried out in the 1970s brought to the light a number of settlements of the Chalcolithic period close to the present village of Ulianovka/Tsitelgori (V. Varazashvili, Rannezemledel’cheskaja kul’turaJuro-Alazanskogo Bassejna [The Early Farming Culture of the Iori-Alazani Basin], Tbilisi: Metsniereba 1992). Two of these sites, which are collectively known in literature under the name of Tsiteli Gorebi, were regularly excavated: Kviriatskhali – Tsiteli Gorebi no. 3 – (V. Varazashvili, 4th millennium BC. materials from the Iori-Alazani basin, in Works of the Kakheti Archaeological Expedition IV, Tbilisi 1980, 18-35) and Damtsvari Gora (V. Varazashvili, Settlement of ,,Damtsvari Gora” Result of the excavations carried out in 1980, in Kakheti Archaeological Expedition’s works VI, Tbilisi 1984, 19-26). Both of them consisted of low single period mounds, no more than 1-1.5 m high, measuring less than one hectare, which yielded abundant ceramic, lithic material and bone objects, but no architectural remains or preserved contexts with in situ material, to the exception of a number of storage pits, a few burials, and some enigmatic ditches. The lack of preserved architectural remains was tentatively explained with the fact that the upper part of the anthropic sequence had been destroyed by ploughing and intensive agriculture exploitation. Other sites in the Tsitelgori microregion were identified as dating to the same period (Tsiteli Gorebi nos. 1, 2, and 4, Shavtskhala, Mtserlebis Mitza, Nadikari, Natsargora) but only cursorily investigated; most of them appear to have been heavily damaged by modern activities. Since then, however, research in the area has been minimal.

This left several important questions unanswered, including, and perhaps most importantly, what is the general chronology of the Tsiteli Gorebi settlements. In fact, although they have been tentatively attributed by the excavators to the first half of the 4th millennium, unfortunately no 14C date could be collected from them. Therefore, their absolute date is uncertain (in fact they could be up to half a millennium earlier). It is also unclear whether they should be considered as strictly contemporary with each other or belong to different sub-periods, especially since parallels drawn by the excavators for their ceramic repertoire spans from the Ceramic Neolithic to the Late Chalcolithic period. Another open question is the relation of their pottery assemblage with the Chaff-Faced Ware tradition: although the excavation reports mention the presence of numerous vegetal-tempered sherds, no typical shape of the Leyla Tepe/Berikldeebi horizon could be recognised among the published materials. Finally, the meaning of this cluster of settlements at a short distance from each other in the framework of the general settlement patterns of the Late Chalcolithic period in Eastern Georgia and their relation with the surrounding general environment is still to be understood.

As we were informed by Davit Kvavadze (head of the local Museum) of the presence of a further, until now never investigated settlement of the Late Chalcolithic period in the Tsiteli Gorebi area, we decided that one of the aims of our first season would be to carry out explorative soundings there. This would allow us to test its potential for larger scale excavations, capable of answering some of the general questions outlined above, during the following seasons. Work at the site started on July 3rd and was closed on July 28th.

The second – and main – aim of the season was to gain a general view of the distribution and state of preservation of archaeological sites in the Lagodekhi municipality. This will involve a multi-year programme of surface investigations, whose ultimate aim will be to analyse developments and changes of the anthropic presence within the region in a longue durée perspective, in their relation with the changing natural environment and in comparison with the neighbouring areas. As a first step in this direction, a short geo-morphological survey of the area was carried out under the responsibility of Prof. Giovanni Boschian, and a preliminary archaeological survey under the responsibility of Dr. Kristen Hopper, assisted by Andrea Titolo. This involved both extensive survey (visiting and recording sites that were identified through published literature, the remote sensing of satellite imagery, and Soviet period 1:25000 topographic maps drawn in the early 1960s and based on aerial photographs from 1954-1955), systematic pedestrian survey of selected 50 m long transects located near the site chosen for excavation (Tsiteli Gorebi 5), and intensive surface collection at the latter.

In spite of the loss of some working days due to the heavy rain which made the access to archaeological sites virtually impossible, the work of the expedition could be carried out regularly and with very promising results in view of its future developments.