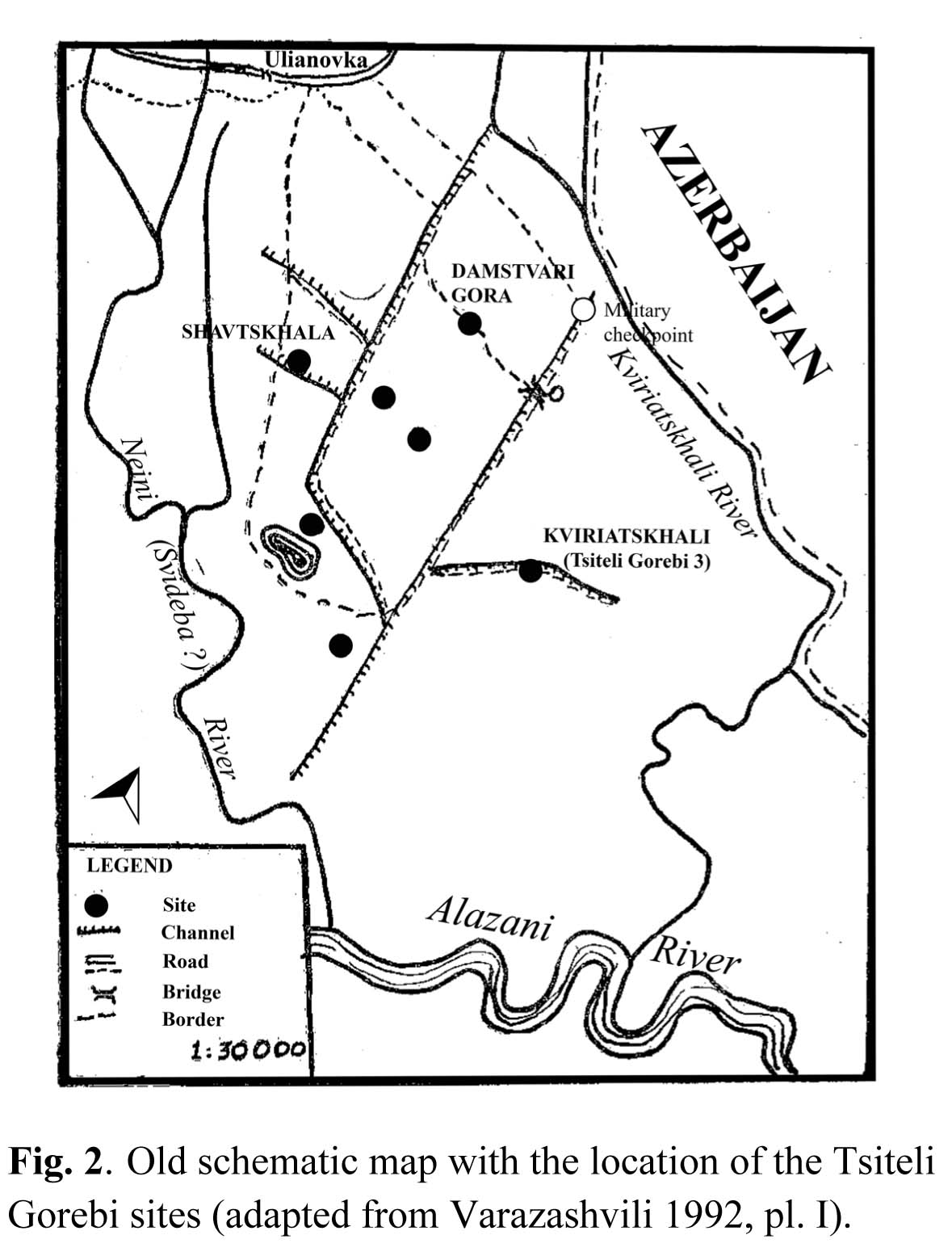

The excavated site belongs to the cluster of Late Chalcolithic sites situated in the surroundings of the Ulianovka/Tsitelgori village. In spite of our efforts, it was until now impossible to locate all the different sites mentioned in the old publications precisely, with the exception of Damstavri Gora, which was unequivocably identified with a presently obliterated site at UTM 38N 596423 E 4616262 N. In particular, we were not able to ascertain the correspondence of the sites indicated as Tsiteli Gorebi 1, 2, and 4 with the dots marked on the plan in Varazashvili's report (Fig. 2). For this reason, we decided to assign the new site where we worked the name of Tsiteli Gorebi 5.

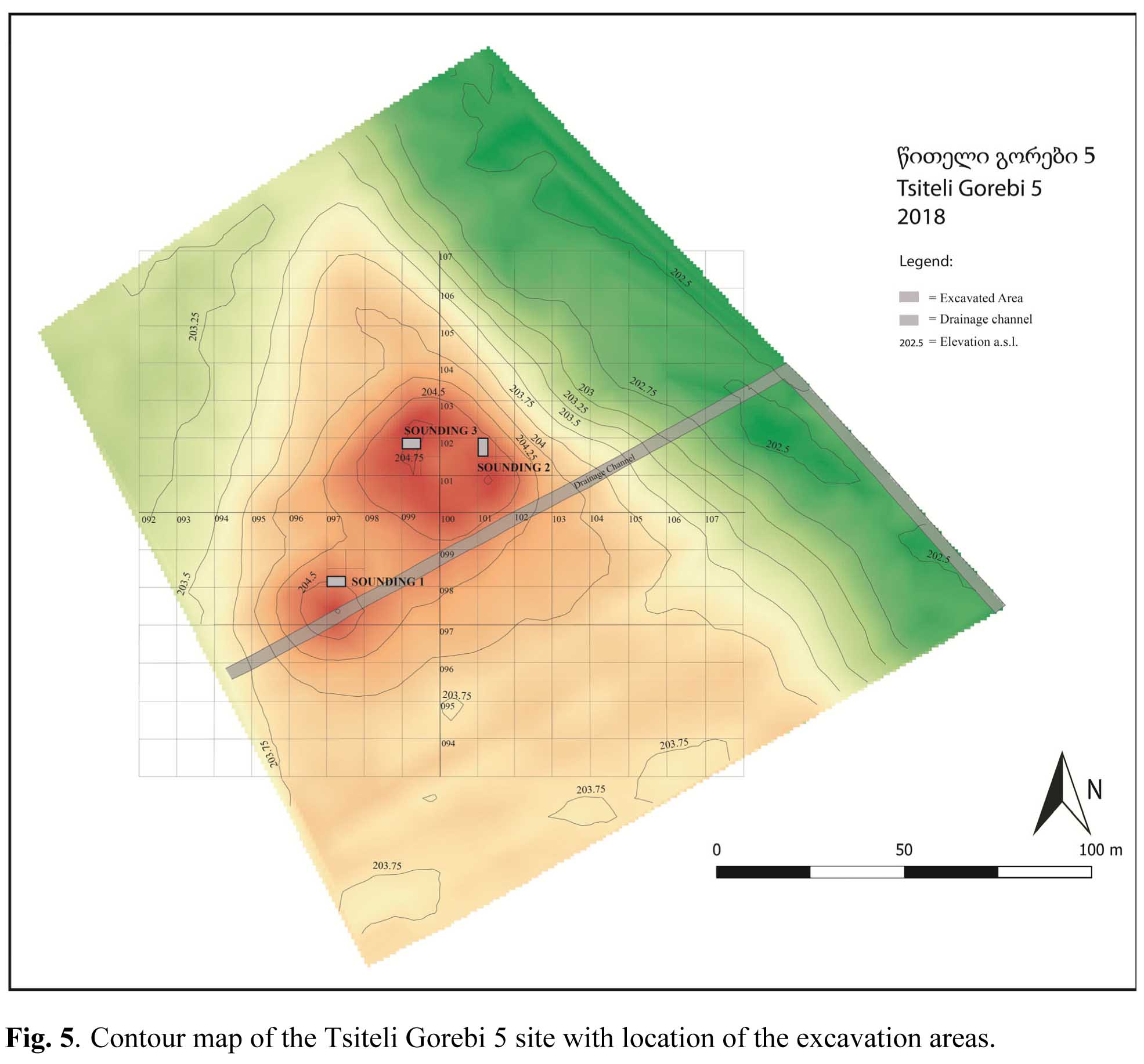

The site corresponds to no. 21 of the Lagodekhi Survey (LS021). It is located at UTM 38N 598828 E 4614070.00 N, in Field No. 56.06.58.221 (cadastre number) belonging to Mr. Vano Mchedlidze. Its maximum elevation above sea level is 204.82 m. It lies in the flat plain ca 4.5 km to the SE of the Tsitelgori village, between the dirt road running southwards from the military checkpoint east of Tsitelgori and the Georgian-Azeri border. The site is presently occupied by a large wheat field. It consists of a low mounded area oriented NE-SW, which emerges of ca 1.30 m on the surrounding plain (Fig. 3). The site has been subjected to repeated ploughing, which probably flattened its top and spread archaeological materials over the surrounding area. It presently occupies a maximum surface of ca 1.60 hectares, corresponding to triangular area of 165 x 170 x 138 m. It is characterised by two low elevations, a larger one to the NE and a smaller one to the SW, separated by a 20 m wide slightly depressed area. A modern drainage channel running SW-NE cuts the site's southern part. The area located beyond the channel is flatter, probably because it has been more affected by ploughing.

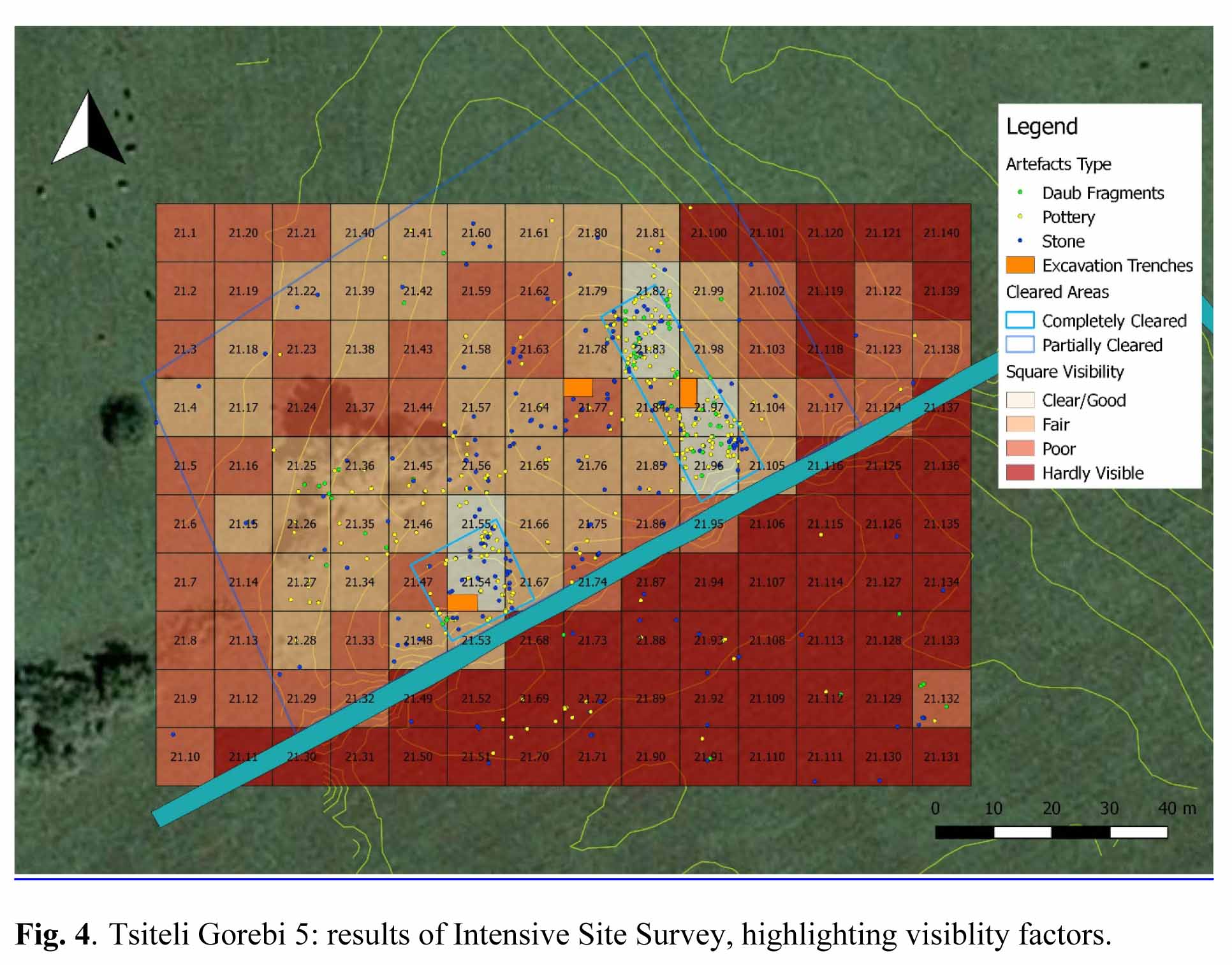

At the beginning of our activities, the wheat field had just been harvested. After removing the wheat stubble, the site was measured and a contour plan of it was produced by differential GPS. During the following days, aerial photographs were also take by drone in order to produce a photogrammetric plan and digital elevation model (DEM) (see Fig. 10). Finally, intensive surface collection was also undertaken over the site's whole surface, in an attempt to more accurately define the limits of the ancient settlement (Fig. 4). In spite of the low visibility due to heavy vegetation, results were quite satisfying, and suggested a maximum extension of ca 2 ha.

In order to choose the most favourable places for placing the excavation areas, advantage was taken of the exposed section along the modern drainage channel, which was cleaned and drawn in three different locations at a distance of 20 m from each other. On this basis, the site's general stratigraphy appeared to be very similar to that of the neighbouring settle-ments excavated by Varazashvili in the 1970s, and to comprise: 1) an up to 40-60 cm thick humus layer disturbed by ploughing, 2) a 20-40 cm thick compact yellowish layer with sparse anthropic remains, 3) an up to

110 cm thick compact yellow layer, almost completely devoid of any archaeological materials, into which some pits (possibly graves) had been dug; 4) a 15-20 cm thick layer of grey-brownish silt, and 5) a brownish-greenish sandy layer. Layers 4 and 5 were completely sterile.

A concentration of sherds and lithic material (mainly obsidian) was observed at the interface between the first and the second layer, suggesting that the relevant occupational levels had been disturbed and almost completely obliterated. The first section from the SW, roughly corresponding to the "secondary mound", yielded particularly abundant material; in addition, three possible pits or graves were located close to it on the channel section. The last section, located in approximate correspondence to the "main mound", yielded less material, but some possible fragments of building material (daub) were located within the otherwise almost sterile layer. On the basis of this preliminary information, we decided to open three 5 x 3 m excavation areas (Soundings 1, 2 and 3) on top of the mounded area (Fig. 5).

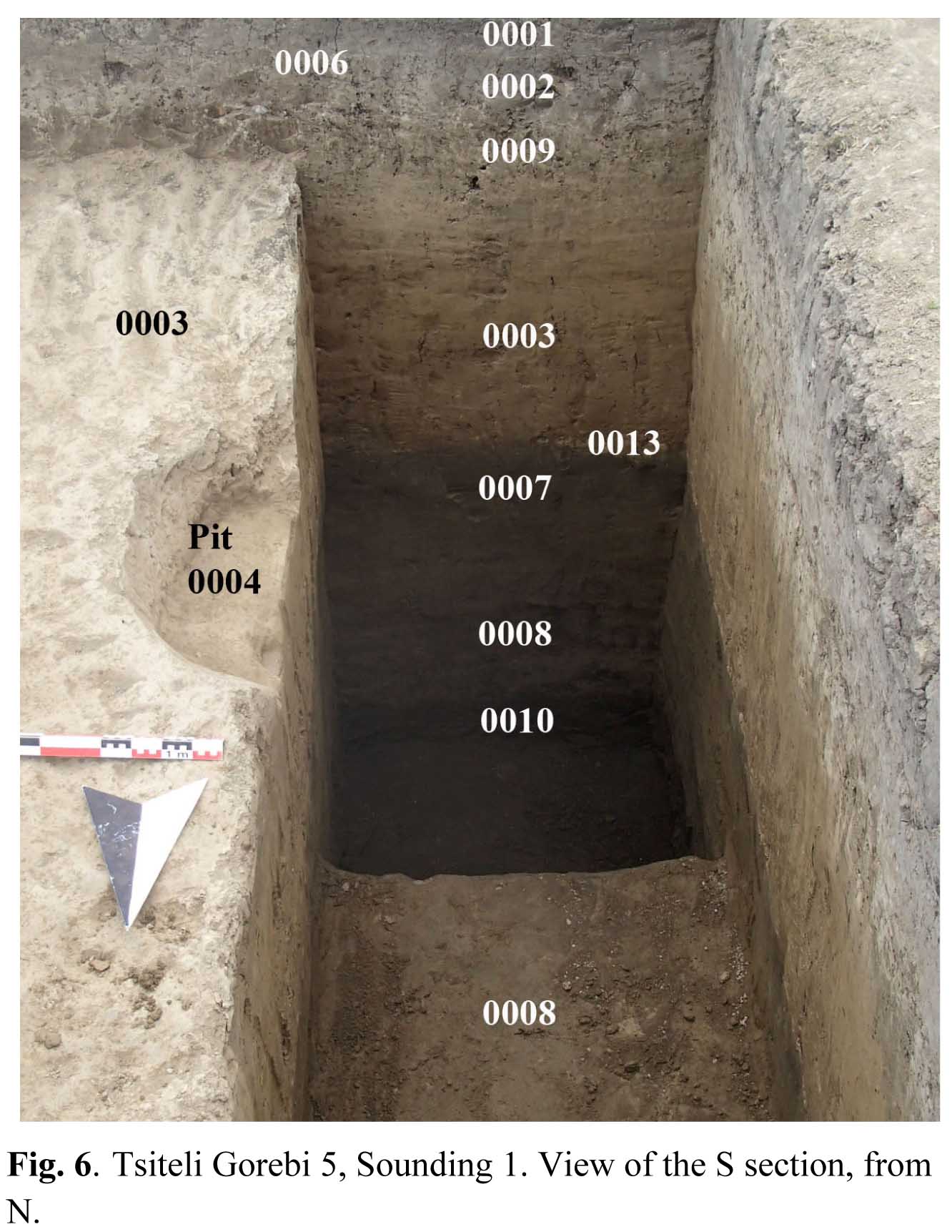

Sounding 1, oriented in EW direction, is located in rough correspondence with the first artificial section, close to the site's western limit and near the top of the "secondary mound", ca 5-8 m N of the drainage channel (quadrant 097.099c), A 2.70 cm thick sequence of layers were excavated, from alt. 204.55 to alt. 201.85 (Fig. 6). Archaeological material concentrated in the uppermost 90 cm of the sequence, the remaining of which was composed of natural deposits.

The 20-30 cm thick surface soil (locus 0001) was underlain by a 10-20 cm thick layer of dark brown soil, still affected by repeated ploughing (locus 0002), which contained small potsherds, obsidian flakes, small daub fragments and animal bones. A special concentration of material was observed at the interface (locus 0006) between this layer and the following one (locus 0009, also 20-30 cm thick), which consisted of clayish soil of yellowish colour with interspersed darker patches, and also contained similar material. Two pits (loci 0004, 0011) had been dug from this layer into the underlying natural soil. This comprised: 1) a 70 cm thick accumulation of yellowish clay (locus 0003), separated by a whitish line (locus 0013) from 2) a 20-25 cm thick accumulation of grey clayish deposits (locus 0007), 3) a 90 cm thick sandy layer of greenish colour (locus 0008), and 4) a very dark grey sandy layer (locus 0010), whose bottom was not reached. The lowest part of the sequence (70 cm) was excavated only on a small sounding measuring 1 x 1 m.

The anthropic sequence was more substantial in Soundings 2 and 3, where virgin soil could unfortunately not be reached at the end of the season due to the unfavourable weather conditions during the last two weeks of excavation.

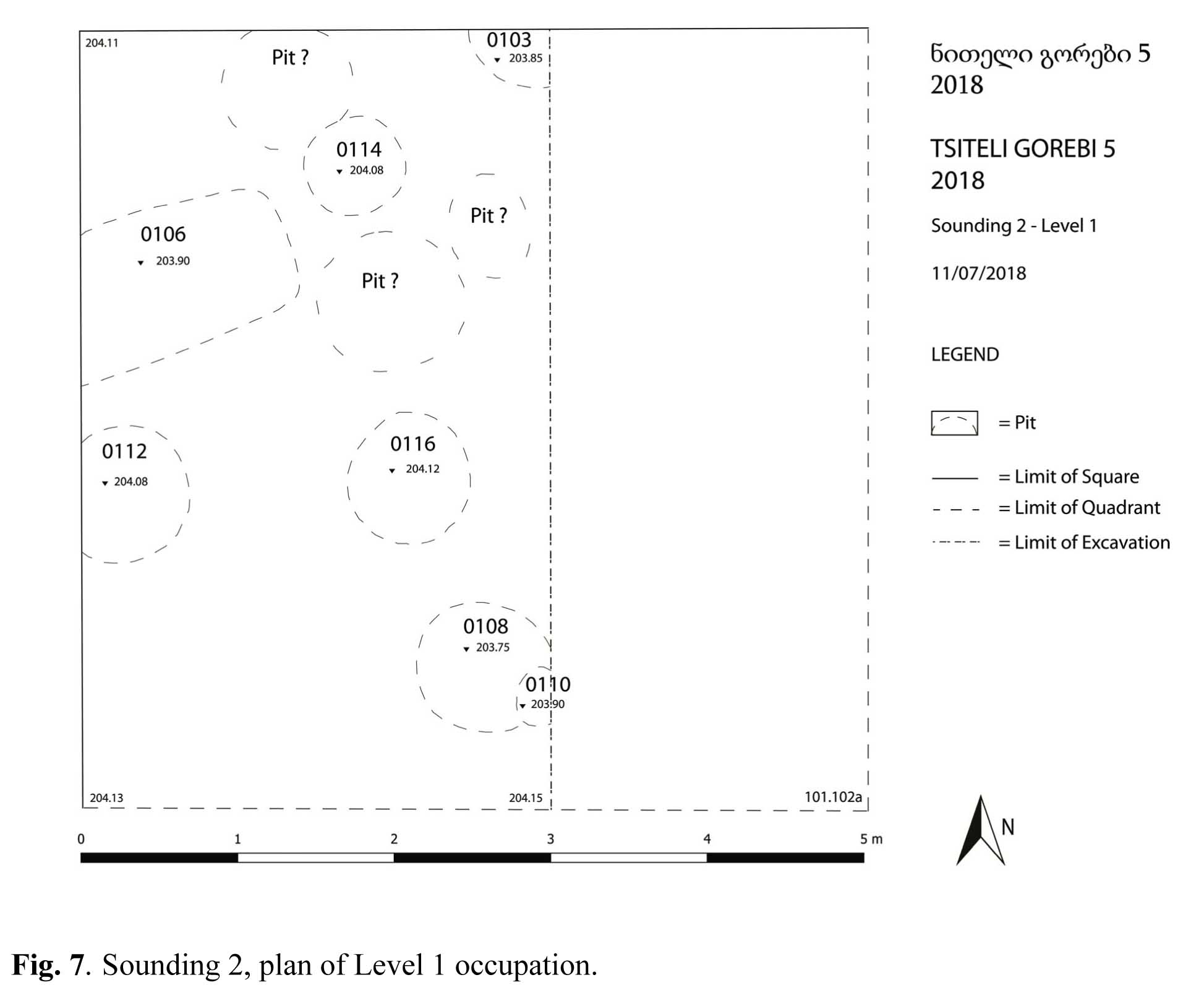

Sounding 2, oriented NS, is located in quadrant 101.102a near the site's eastern limit, at a distance of 40 m from Sounding 1 and 19-20,5 m N of the drainage channel, close to the third artificial section. The surface and subsurface layers (loci 0101, 0102), were severely disturbed by ploughing, but yielded exclusively Chalcolithic artefacts. They reached a total depth of 35-50 cm from the top soil (which lay at a max alt. of 204.74 m a.s.l.), and were underlain by a filling (locus 0118) of yellowish clayish soil, into which several pits of different shapes and dimensions had been cut. The largest of them, locus 0106, had a rectangular shape with rounded corners; its filling consisted of compact grey soil. The remaining pits were smaller, and mostly of rounded shape. All of them contained very little material; this was exclusively of Chalcolithic date, although we cannot absolutely exclude that the pits had been dug at a later time. Be that as it may, they have been considered to belong to the same general level (Level I) (Fig. 7).

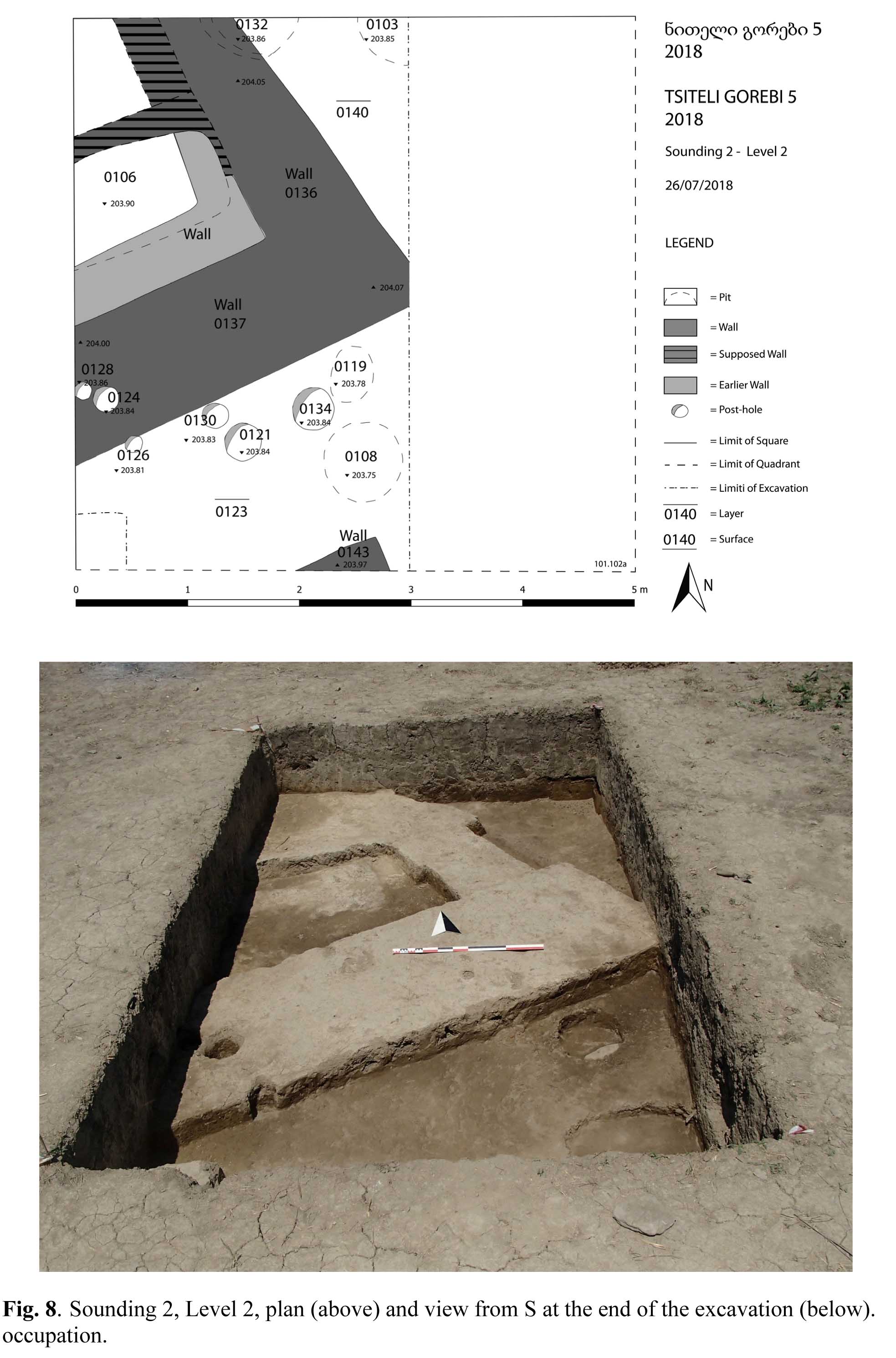

The top of the next level (Level 2) lay at approximately 204.00 m a.s.l. (Fig. 8). The level was not only cut by several pits (loci 0132, 0119, in addition to 0103, 0106, 0108 from Level I), but also by three couples of post-holes of different dimensions: 0121 and 0134 (diameters 27 and 34 cm), 0124 and 0130 (diameter 22 cm), and 0126, 0128 (diameter 15 cm), whose meaning is not clear; they may represent what remains of an occupational layer which has completely disappeared.

Level 2 was characterised by a clear distinction into areas of darker, softer soil (loci 0123, in the SE part of the excavated area, 0140, in its NE corner, and 0141, to the S of the cut of pit 0106), rather rich in finds, and an irregular area of harder, yellowish compact soil, which extended over its central part. Upon careful cleaning, this turned out to represent the degraded top of two large clay walls (loci 0136 and 0137) running perpendicular to each other in NW-SE and respectively SW-NE direction. The faces of the walls were not to be clearly outlined, but the change in colour and texture of the sediments was quite clear, as the walls consisted of almost pure compact clay of yellowish colour. An area of yellowish soil within filling 0123 leaning against the S face of wall 0137 may represent what was left of a possible buttress protruding from it. There probably was a third wall making a corner with 0136 and running parallel to 0137 ca 80 cm to the N of it, which had been almost completely obliterated by pit 0136. A small part of another possible contemporary wall (locus 0143) was found in the SE corner of the sounding; interesting enough, from what could be seen in the section this may have been formed of quadrangular blocks of clay ("bricks") of squarish shape.

The fillings of Level 2 were excavated down to alt. 203.90-85 without reaching the base of the walls and without encountering any floor or surface; as a consequence, it is impossible to know at what height the walls were preserved and whether they had been built directly on the virgin soil or rested on an earlier anthropic level, as the presence under the bottom of pit 0106 of a rectilinear limit with slightly diverging orientation from the Level 2 walls may lead to suppose.

Sounding 3, oriented EW, lies in quadrant 099.102a, 15 m west of Sounding 2, on top of the "main mound", close to the site's highest point. The present surface is slightly sloping in eastern direction, from alt. 204.84 to alt. 204.69. The surface layer (locus 0201) is ca 20 cm thick, composed of dark brown, soft, homogeneous soil. It overlays a ca 20 cm thick subsurface layer (Loci 0203, 0204, 0217) of similar texture but more greyish in colour. This upper part of the stratigraphical sequence appears to be rather disturbed; this is the only sector of the excavation where, besides a large majority of Chalcolithic artefacts, a few later materials (some iron fragments, one possible Bedeni sherd) have been recovered.

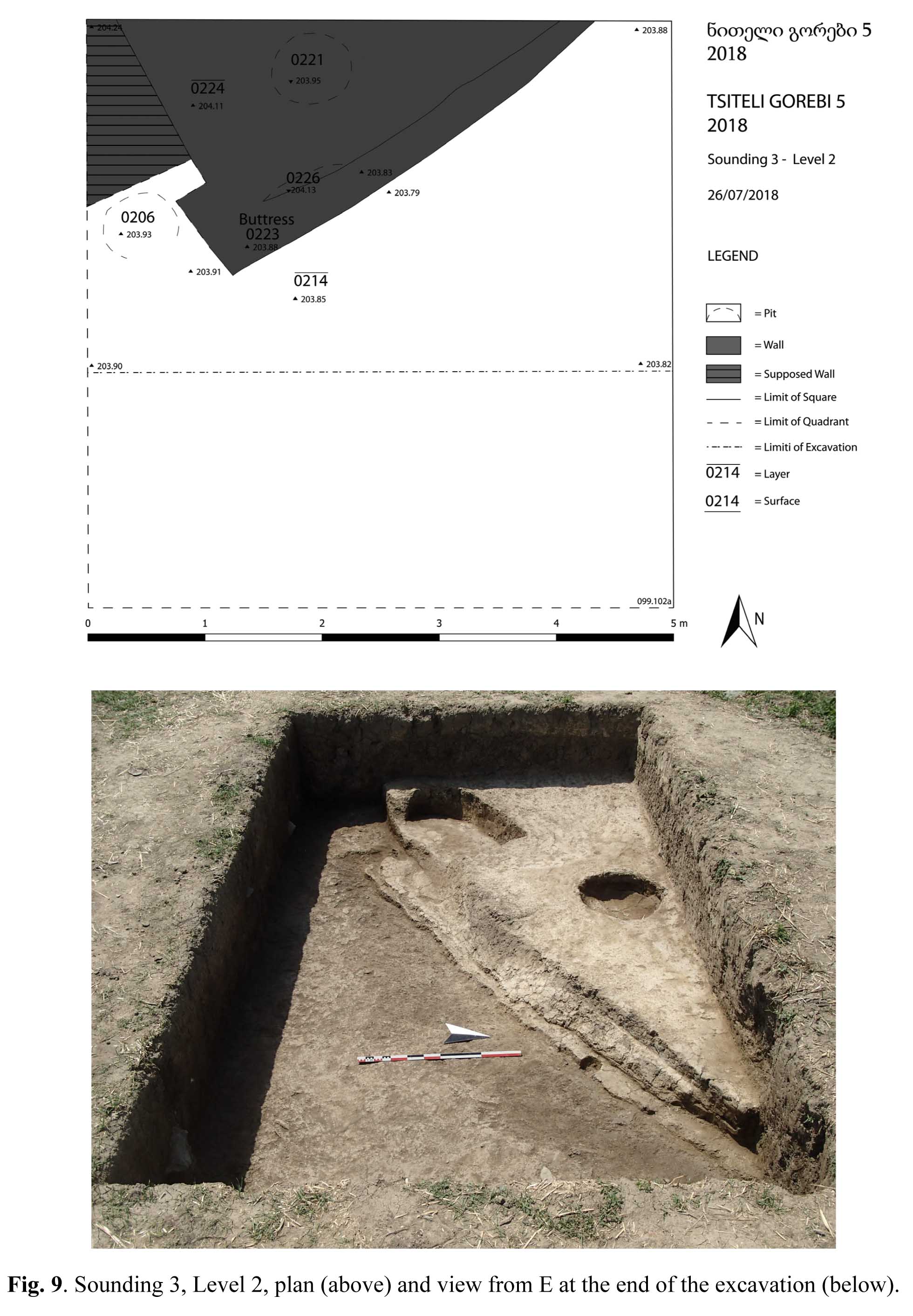

A less disturbed archaeological level (Level 2) was met with around alt. 204.35 (Fig. 9). This was cut by a number of pits (0208 in the centre of the N part of the sounding, 0210 in its NE corner, 0212 in its SE part, and 0215 at its E limit), which had probably been dug from a later level, and the upper part of which had been completely lost (Level 1). The southern part of the excavated area was occupied by a filling of dark brown, soft soil containing some fragments of yellow clay (locus 0214). This contained abundant Chalcolithic pottery, obsidian flakes, animal bones, and a pendant. The recovery of an iron object and of a fragment of Medieval glazed pottery suggests that either the layer is still partially mixed, or that a pit has been missed in the course of excavation. The northern part of the excavated area was occupied by a nearly triangular area of hard, compact, yellowish clay (locus 0220), separated from filling 0214 by a line running in SE-NW direction.

Locus 2200 represented the damaged top of a large platform (Locus 0224), which continued the trench. It at least partially composed of brick-like blocks of clay of different colours (dark brown and yellow) measuring 16 x 16 or 16 x 10 cm (Fig. 10). The face of the platform was difficult to articulate, but it is clear that it made a corner near the western limit of the excavation area.

The excavation of filling 0214 was interrupted at alt. 203.91 without reaching the base of the platform and without discovering any floor associated with it.

In spite of the slight differences in the stratigraphy of the three excavated soundings, it is clear that archaeological layers over the whole settlement area had been deeply affected by a combination of different post-depositional elements, among which not only deep-ploughing, but also earth-worms activities and repeated flooding appear to have played a prominent role. The resulting homogeneisation of the sediments caused the dislocation of arte/facts from their original position, a severe loss of site's stratigraphy and a low visibility of the still existing architectural structures. Artefacts and ecofacts collected at the site were mostly in a bad state of preservation (almost no organic materials had survived, pottery sherds were quite small and rather damaged, animal bones were on the whole well preserved, but heavily mineralised and in small fragments).

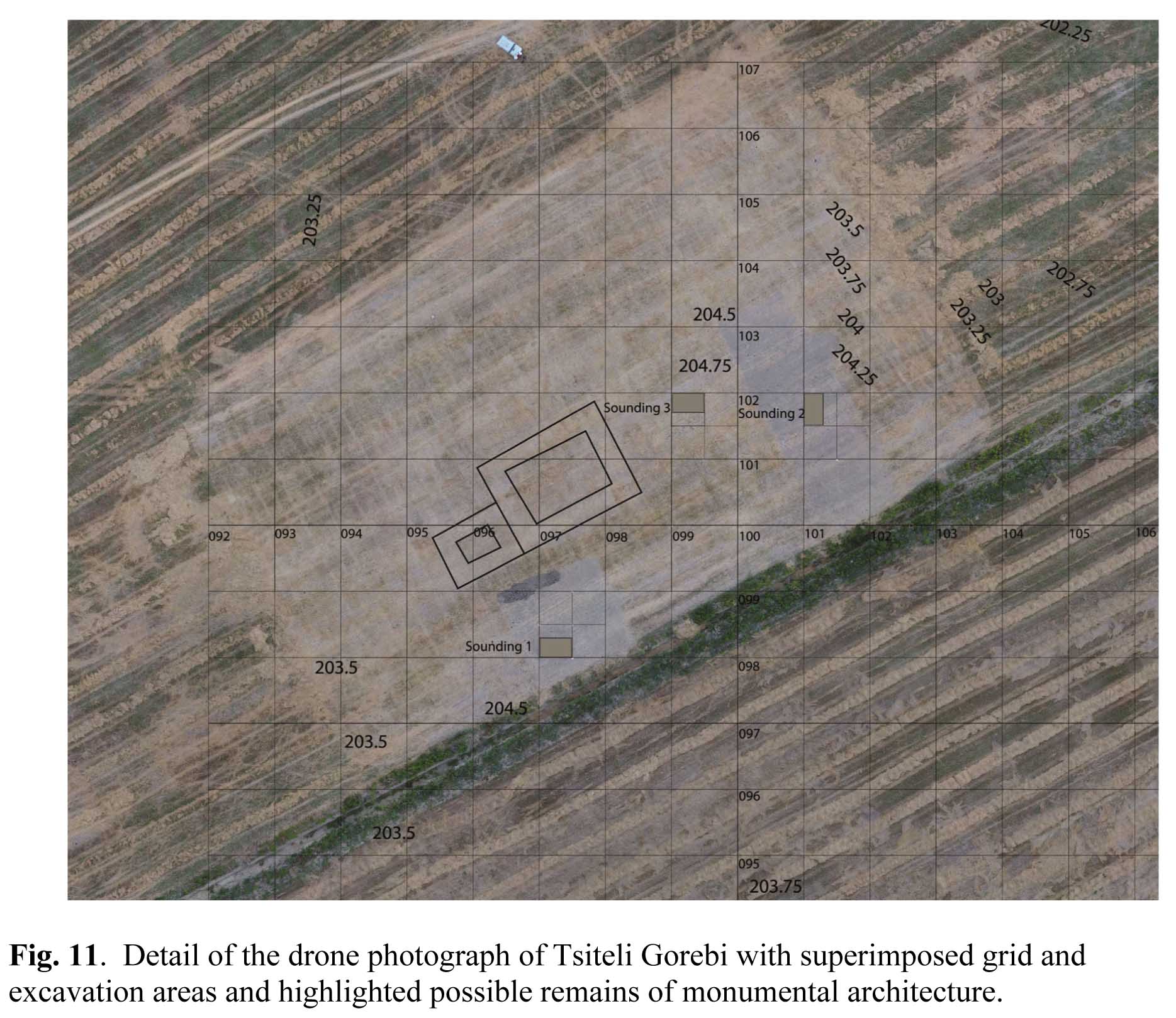

This unfavourable conditions are clearly a general feature of the Tsiteli Gorebi microregion, as they find a precise correspondence in the descriptions of the previous excavators working in the area. They provide a reasonable explanation of the fact that no architectural remains had hitherto been noticed at these settlements, and invite to caution in drawing general conclusions about the ways of life of the ancient population from their apparent absence. On the other hand, it is hoped that awareness of this problem and an increased attention in the course of excavation may result in the future discovery of other poorly preserved architectural remains. In fact, the considerable dimensions of the walls and platforms uncovered in Soundings 2 and 3 might suggest the presence at the site of large-scale architecture. Another hint in this direction are some rectilinear marks visible in the drone photographs of the site to the NE of Sounding 1 (Fig. 11). In fact, if these indeed correspond to ancient structures, which is doubtful because they run suspiciously parallel to modern ploughing bands, their length would reach up to 20 m ca.

On the basis of a preliminary analysis, the artefact assemblage recovered in the three soundings appears to be quite homogeneous and almost identical in composition to that of the previously excavated sites of the Tsiteli Gorebi cluster (Kviriatskhali and Damstavri Gora), and to find more general parallels at various sites of the so-called "Sioni-Tsopi" cultural complex (see A. Sagona, The Archaeology of the Caucasus, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2017, 203 ff.; B. Lyonnet, Rethinking the ‘Sioni Cultural Complex’ in the South Caucasus (Chalcolithic Period): New Data from Mentesh Tepe (Azerbaijan), in A. Batmaz et al. (eds.), Context and Connection: Essays on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East in Honour of Antonio Sagona, OLA 286, Leuven 2018, 547-567; L. Nebieridze, The Tsopi Chalcolithic Culture, Studies of the Society of Assyriologists, Biblical Studies and Caucasiologists 6, Tbilisi: Artlines 2010).

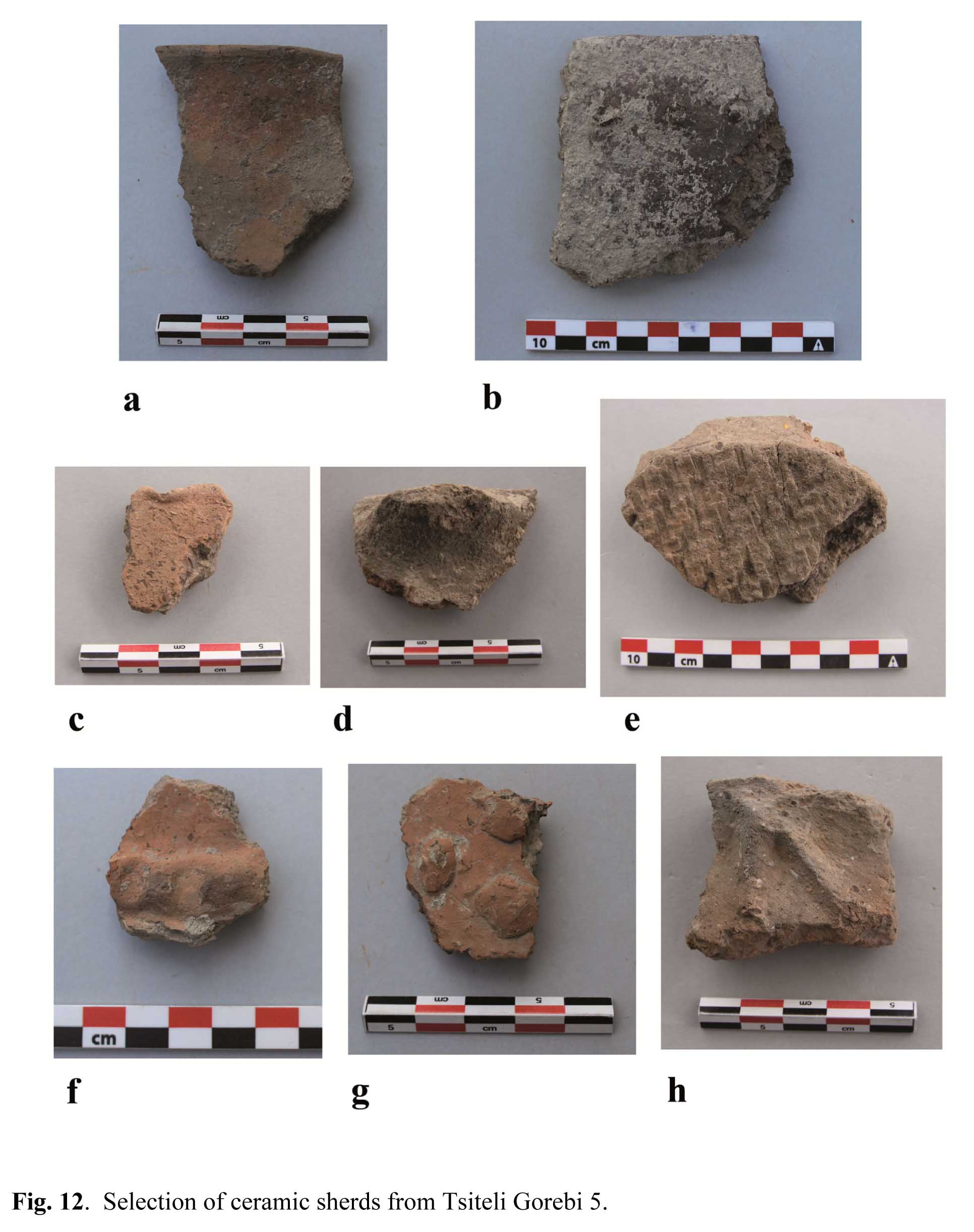

Pottery (information provided by Laura Tonetto) is quite homogeneous in fabric, morphology and decoration (Fig. 12). It is always handmade and of very coarse quality; walls are generally rather thick, even if some fragments with a thinner wall, generally belonging to small vessels, have been observed. The fabric is invariably characterised by the presence of a large amount of mineral inclusions of medium or large size. Interestingly enough, no fragments of "Chaff-faced Ware" have been recovered, and occasional vegetal inclusions have been observed only in three sherds.

In spite of the overall fabric homogeneity, sherds have been tentatively divided into three different ware groups (Light Brown/Orange Ware, Red Ware and Grey Ware) mainly on the basis of fabric and surface colour and surface treatment. Light Brown Ware is the most frequent (447 fragments, less than 10% of which are diagnostic types). The fabric is mostly fully oxidised, although some sherds exhibit a grey core; the outer surface is orange or brown with yellowish shades (5YR 5/4 reddish brown, 5YR 6/6 reddish yellow). Sometimes the surfaces are smoothed and covered by a brown slip. With 132 sherds, only 5 of which are diagnostic types, Red Ware comes next in frequency. Its fabric is fully oxidised. Examples are characterised by a reddish surface (5YR 5/6 yellowish red, 5YR 4/6 yellowish red); the surface of fragments belonging to small-size vessel is often carefully smoothed and sometimes covered by a reddish brown slip and/or slightly burnished. Grey Ware is the least common, being represented by 101 sherds, about 10% of which are diagnostic types. The surface has a grey colour (GLEY 1 6/N grey, 5Y 3/2 dark olive grey) and is only rarely smoothed; the core is reduced.

As far as it is possible to judge (most sherds are very small and cannot be attributed to a precise vessel type), there are no significant associations between these wares and specific shape types. The morphological repertoire is rather limited: the most common types appear to have been large deep bowls with slightly curved walls and plain rims, and wide-mouthed pots with slightly outturned or vertical rims (Fig. 12a). Also well attested are high straight-walled trays provided with a line of holes made before firing in the upper part of the wall (so-called mangal) (Fig. 12b) and hole-mouth jars. Rims with flattened tops and elongated lug-like ledge protrusions (Fig. 12c) are relatively common, whereas there are only two rims which show nail impressions and two finger-impressed ones (Fig. 12d). Bases are generally flat or flattened; some of them show mats impressions on their lower surface (Fig. 12e).

Decorations are rare and mostly consist of small circular knobs in relief (Fig. 12f); two sherds exhibit rows of notch-like impressions (Fig. 12g) and two sherds are characterised by relief patterns reminiscent of those characteristic of the Shulaveri-Shomu culture (Fig. 12h). No example of painted decoration was recovered.

Besides observing the similarity of this material with that recovered at Kviriatskhali and Damtsvari Gora in the 1970s, it is difficult to attribute a precise relative date to it. The total absence of "Chaff-Faced Ware" and the presence of decorations in the Shulaveri Shomu tradition, together with the rarity of incised rims, which represent an hallmark of the Sioni culture, would suggest a rather early date within the Chalcolithic period, i.e. much earlier than the 1st half of the 4th millennium BC (Late Chalcolithic) suggested by earlier excavators. Parallels with recently excavated material from Mentesh Tepe (especially Period 2 and, less so, also Period 3) material, associated with 14C dates (B. Lyonnet, Rethinking the ‘Sioni Cultural Complex’ in the South Caucasus, cit., 554-561; eadem, in B. Helwing et al., The Kura Projects. New Research on the Later Prehistory of the Southern Caucasus, Archäologie in Iran und Turan 16, Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag 2017, 144-147) may in fact suggest a date in the first half of the 5th millennium.

The lithic assemblage (Fig. 13) is almost exclusively composed of obsidian, with a small component of tools of dark grey quarzite or microcrystalline rocks of volcanic origin, and a very small amount of flint tools (bottom right). Obsidian occurs in different colours – from almost transparent to opaque –, in various shades of grey and black and brown-speckled. This may suggest that different sources were used by the local population, but only provenance analysis will be able to confirm this hypothesis. The majority of the assemblage consists of unretouched flakes, some of which show possible use wear. The remaining items are irregular tools on flakes or blades, which exhibit a not very accurate marginal, steep, or semi-steep retouch. Most of them may be described as generic blades-scrapers. The presence of a few nuclei (bottom centre) and of numerous small flakes suggests in situ processing of the raw material.

A stone mortar and several bone awls obtained from half-sectioned metacarpal bones of caprines and bovines (Fig. 14) deserve being mentioned among the very few remaining finds.